Introduction

The article “Comparing the Effectiveness of Classroom and Online Learning” by Ya Ni (2013) focused on comparing the effectiveness of two distinct delivery methods, a topic not dissimilar to the report by the Department of Education (2010). Unlike that report, which was a statistical meta-analysis of several different platforms and approaches, this study focused on the analysis of a single course by the same instructor, taught in both modes of instruction, with the purpose to determine if the method of delivery influenced student performance as measured by the grade achieved.

While the availability of online courses has been rapidly expanding over the past two decades, the primary purpose of this specific analysis was connected to the need to respond to accountability requirements as specified by educational accrediting bodies. In this instance, accreditation is provided by the Network of Schools of Public Policy, Affairs, and Administration (NASPAA), an appropriate choice, given that the course used in this instance was a graduate course in public administration.

The article extensively discusses the components of both types of class delivery. Their discussion focused on the differences of the social and communicative actions between student and teacher and student and student, performance as measured by grade, student attitudes about learning, and their overall satisfaction with the course. It also discussed potential differences in learning persistence in the two different platforms.

Review of Analytical Methods

The course selected for this analysis was Research Methods in Administration. This course was a required course for the Masters in Public Administration (MPA) at the California State University – San Bernardino at the time the study was completed. The course is offered as both in-class and online format. Students select their method of delivery based on many factors including commuting distance, working schedule, and tuition difference (Note. At that point in time, there was an additional fee for online courses). The study evaluated the delivery of this course by the same instructor over a two year period and included three deliveries of the same course in each of the two delivery methods.

Data collected from each of these 6 classes included the student performance records (e.g., grades) as well as student survey responses from two (one online and one classroom) of the six classes. Both online and classroom participants were given access to the Blackboard system for the purposes of submitting assignments and receiving feedback. The article did not identify if the online course was presented synchronously or asynchronously.

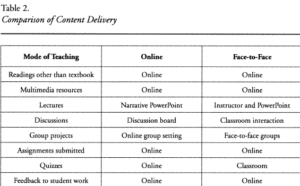

Table 2 of the article presents the comparison of content delivery for the course

The two hypotheses evaluated are presented as:

- H0: there is no significant difference in learning effectiveness between online and face to face classes

- H1: Online class differs from face to face class in learning effectiveness.

Learning effectiveness is presented as the dependent variable. Grades, voluntary student self-evaluation of achieving learning objectives, and student assessment of online interaction are used to evaluate course effectiveness in each medium.

It was not clear if the author was the instructor, which could lend some bias to the study.

Results

The statistical method used to initially evaluate these hypotheses was the Chi-Squared test of independence. The analysis initially evaluated outcomes both with the inclusion and the exclusion of Incompletes. Both analyses indicate that learning effectiveness is independent of the mode of instruction, suggesting that there was sufficient confidence in the observed differences between the two delivery platforms.

Given that this is a course that is often taken at the beginning of the program, it is not unexpected that those who failed would subsequently abandon the program. Related analyses on other courses in the program suggest that this course is the “weed-out” course, given that students were more likely to fail in online research methods classes than in any of the other online core courses including public financial management, public budgeting and finance, and public policy analysis.

The author also reflected on a few design flaws in the research. Learning objectives were provided in both classes and may have been emphasized a bit more in the classroom setting. The timing of the student survey was different for each of the two classes evaluated – one being 3 weeks before the conclusion of the semester and one at the end of the semester. Students who failed the course in either platform could have influenced the results which could not be adjusted since the surveys were anonymous.

Discussion

Despite the small sample size of 6 classes and 148 students for this analysis, the study did an excellent job of controlling for several variables. Referring back to Table 2, four of the eight variables were consistent, further reducing potential variability in the study. As stated within the paper, “learning effectiveness is a complex concept with multiple dimensions; it should be assessed with multiple measures”.

Despite the use of a very structured approach, there is a bit of interpretation in their discussion. One of their key conclusions was that “learning effectiveness is a complex concept with multiple dimensions and should be assessed with multiple measures.” In fact, it seemed that they reversed their assessment of the Chi-Squared analysis discussed above as they concluded that there were no significant differences in the outcomes between the online and classroom classes. Rather, they suggested that these results demonstrated that there were observable differences in the student’s persistence rate and assessment of interaction to suggest that the two instructional modes can yield different results. The author uses this assessment to voice their support for additional studies.

The author spoke to a number of factors that could have influenced the results. This program employed the use of pre-enrollment counseling and post-enrollment advising to assist students both in determining if this program was the right fit for them as well as the best way to achieve their objectives, which had the impact of ensuring that there was a greater likelihood that the students selected for the program would finish the program. The study focused on graduate students, whose focus on completing their degree and time management skills may be greater than other groups of students.

I found the true value of this article to be in their discussion in making online instruction more effective. Given that the study focused more on application than theory, it would be reasonable to assume that once their questions about baseline effectiveness had been met, that they would move on quickly to thinking about other areas that could be evaluated. For example, were there instructional design strategies that would enhance learner persistence that would be different in online vice classroom presentations? Are there some courses that are better suited for online learning than others – similar to the conversation that we’ve had in class about teaching dental students online?

Conclusion

I had a great appreciation for how the study was designed in that there appeared to be a lot of rigor. As this study was only three years after the Department of Education Report, this suggests that the move towards online learning was continuing to increase.

This article brought me back to thinking about assessment in general. For example, there was no apparent connection to using the Kirkpatrick model, initially released in 1996. Perhaps that is because the study was treated more as a statistical evaluation, but it would have been interesting to see how they thought their assessment strategy integrated into a common model. And that raised another question for me – is there a connection between measuring learning effectiveness and accreditation requirements. That is a topic for another day.

One of the things I’ve learned from evaluating this article is that the assessment strategy should be built into the course delivery from the beginning – reminding me to begin with the end in mind, a strategy made famous by Stephen Covey. This article was an interesting reflection on how far we have come in considering the variables that contribute to online learning. It was interesting to see how integrated it was with the various learning theories we covered last week.

It was not lost on me the irony of how COVID-19 has driven us all to online presentations, including the NASPAA’s Fall Conference, which will be offered virtually this year. I wonder how NASPAA will measure the effectiveness of moving to an online environment for conferences.

References

Ni, A. Y. (2013). Comparing the Effectiveness of Classroom and Online Learning: Teaching Research Methods. Journal of Public Affairs Education, 19(2), 199-215. doi:10.1080/15236803.2013.12001730