Introduction

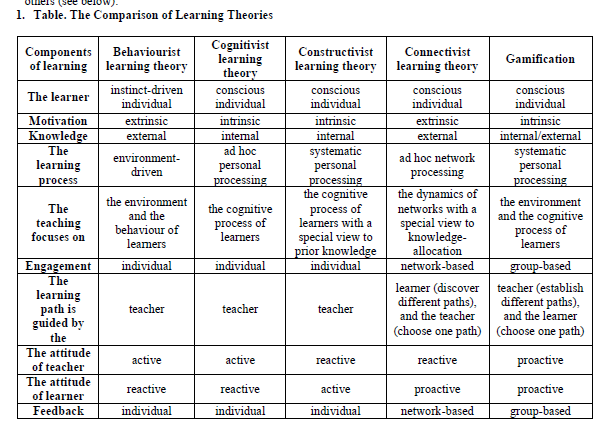

I found Biro’s Table of The Comparison of Learning Theories as I was looking for articles on gamification. In that article, Biro boldly proposes that gamification should be considered as the fifth learning theory accompanying the current primary theories of behaviorist, cognitivist, constructivist, and connectivist. Note that I say primary since there are several schools of thought around learning theories as evidenced by this image.

While reviewing the article by Biro (2014), I found another article by Skuta and Kostolanyova (2016), which referenced the article by Biro as being one of two key papers cited by other education researchers, the other being a book by Karl Kapp (2012), not reviewed here.

These two articles appeared complementary in that Biro’s paper suggests the theory and Skuta and Kostolanyova’s paper tested the theory, using an application using Duolingo as the example. Given that I have used Duolingo for 3 years, I decided that this would prove to be an interesting perspective to evaluate whether I concurred with these authors’ assessment.

Evaluation of the papers

My initial challenge in selecting these papers was in determining whether or not I thought either of these papers could be considered research papers since neither used experimental research methods such as those outlined in standard educational research books. However, if one uses guidance provided by the Dewitt Wallace Library, one could suggest that both papers provide a form of observational data as consideration for readers’ subsequent analysis.

From a credibility perspective, Biro’s paper is from a peer-reviewed journal and released under a creative commons license. The methodology for Biro’s paper is appropriate as it represents the seminal work in advancing this hypothesis for consideration by others.

Skuta and Kostolanyova’s paper was presented at a conference on distance learning in applied informatics and therefore, is probably less critically reviewed as it focuses on reporting on their presentation. Their article indicates that their aims include collecting data that might be used to support Biro’s hypothesis, identify challenges in pursuing this type of research, and completing an analysis as an example of how future work could be conducted. The methodology for Skuta and Kostolanyova’s paper is also appropriate, and even somewhat apologetic for not being more detailed due to the space limitations of the printed proceedings.

Analysis of the papers’ findings

Starting with definitions, gamification is differentiated from games in that game-like features or designs are added to non-game contexts. Gamification is clearly a new field of study, especially when considered with the likes of Skinner, released almost a century ago.

Some suggest that while the field started with the advent of computers and subsequent computer games in the 1980s, the application of game-like features and design for educational purposes is far more recent as these papers suggest. Given the level of (im)maturity in this field, it is inherently reasonable to expect that the initial papers that are helping to define the field would not have robust data to support them.

While perhaps not quite a fair analogy, one could argue that Darwin’s “On the Origin of Species” was based on the power of observation, as he based his hypothesis on evidence collected during his voyage on the Beagle although he supplemented his theory with additional experimentation. Biro is supporting his hypothesis through the use of evidence as built through the use of a compare and contrast table leveraging several components of learning. While I think that both authors are strongly impassioned about their work, Biro conveys his thinking with less attachment to changing people’s minds to accept the theory than to invite others to consider it and test it themselves.

I was intrigued by Biro’s clear use of the word ‘Didactic’ rather than ‘Pedagogy’ to support his theory. Didactics is described as the art or science of teaching while Pedagogy appears to focus more on the instructional design. It was also amusing to see him use the reference ‘2.0’, suggesting a similarity to our current vernacular of version releases. And the use of a creative commons license clearly communicates a desire to encourage the conversation. It appears that these are both used as “hooks” to pull in the reader to focus on the call to action in his final paragraph on the future of learning sciences. Indeed, he acknowledges that additional research in this field could provide the empirical data required to support the increased use of this particular learning theory. Ultimately, he leaves it up to the reader in his closing sentence of “You decide”.

At the moment, I’m not convinced there is a compelling case to consider gamification the fifth learning theory, especially when one considers that there are several permutations to the branches on this tree of learning. I think of learning theories as useful tools in the toolbox, but not ones that should constrain our thinking. In this instance, I am thinking of the concept of “just because I have a hammer does not make everything a nail”. I currently look at gamification as a tool that can impact motivation more so than how someone might learn. However, future research may prove me wrong. At any rate, I still find the concept of gamification to be a useful one to consider as I think about building my proposed curriculum.

Which then brings me to the second article of applying the theory to practice – in this case, the use of Duolingo. I have intimate knowledge of Duolingo, having used the app to practice Spanish daily for 3 years or 1095 days. Note that one only gets a badge for 365 days of continuous use. My period of practice extended from May 2017 to May 2020. That means that my experience with the tool is later than the tool described in the paper and that I have seen the tool go through several iterations. The paper is appropriate for how the product existed at the time. Therefore the challenge for this research paper is not that it is poor quality or that the research doesn’t have value. It is more than a review of an application in this field that will, by definition, be overtaken by events much more quickly than the theory itself. This is why the paper lends itself to be part of conference proceedings more than a peer-reviewed journal. The data is good for a period of time and then loses some of its value. While it was a good description of the game elements and game design of the app at the time, I did wonder if they had actual experience with the tool that they were reviewing in terms of how it might have motivated them and made them feel while they were learning. The real value of their work may come from the intangible and immeasurable benefits of inspiring others to pursue similar analyses.

My personal experience with Duolingo was that the game-like qualities did encourage me to spend more time with the app. During those 3 years, the badges changed and the format was updated – not frequently, but at least twice over the 3-year time frame.

My motivation also changed over the course of three years. Initially, I was completing this activity as a 10 point daily goal as one of my morning pastimes while on the Metro to work. Eventually, I realized that I wanted to listen more than just read the words, so I changed this to one of my morning past times during coffee since the noise on the train didn’t accommodate my new goal. When I started competing with friends, I found that I needed to look for long stretches of time to hit some of the leaderboard badges, such as when we were traveling in the car to see family. There are 5 levels to each lesson and I was on my way to working through all of level 3 when I stopped. One of the key reasons I stopped was that while I could recognize the words and put sentences together, it wasn’t helping me to learn how to speak the language. So this particular activity is on hold until such time as I finish my master’s degree.

Closing

As a first foray into this area, I found that the papers and the research had value – at least for me. The conclusions were appropriate for the time and place of this topic, given its lack of maturity and extensive growth potential. The papers posed more questions than they answered and I believe that to be their purpose. I also found it intriguing that both of these papers were by authors from Hungary and the Czech Republic, demonstrating that this issue is certainly a cosmopolitan one.

References:

Bíró, G. I. (2014). Didactics 2.0: A Pedagogical Analysis of Gamification Theory from a Comparative Perspective with a Special View to the Components of Learning. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 141, 148-151. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.05.027

Petr Škuta, & Kateřina Kostolányová. (2016). The Inclusion of Gamification Elements in the Educational Process. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.1.3026.7766